Evaluating history, or solving it? Thoughts on the epistemology of historical “discoveries”

Epistemology of Historical "Discoveries"

Last month, a paper published in Nature explored how large language models (LLMs) could be used to enable new discoveries in mathematics. The authors, primarily affiliated with Google DeepMind, propose a search function that may improve AI’s capacity to expand the boundaries of what is knowable – rather than merely replicating or reformulating material derived from the data on which the model was trained, or hallucinating “knowledge” that looks like something verifiable, but which doesn’t stack up when confronted with a human assessment of the result.

While their core proposals are beyond the scope of Historica (or, indeed, my own expertise) in applying an LLM to problems in combinatorics – the branch of mathematics concerned broadly with counting, arranging and sets – I was struck by their first line: “many problems in mathematical sciences are ‘easy to evaluate’, despite being typically ‘hard to solve’”. This distinction, of course, has a precise meaning in mathematical analysis: in simplistic terms, to evaluate is to ask how good a given solution is to a problem (“measuring the quality of the solution”), rather than to establish a single solution from a defined group of starting parameters.

The Challenges of Applying Mathematical Concepts to History

History, of course, doesn’t fall into this neat epistemological division. Despite the riskiness of applying a mathematical concept to a field that cannot admit difference in those terms, the distinction between evaluation and solution struck me as nonetheless indicative of an error easily built into questions asked of history, and consequently the kinds of things machine learning can do when applied to the past. Despite the pretence underlying attempts to resolve, or understand, historical phenomena (“what were the causes of the First World War?”), history can never be “solved”, precisely because it ultimately details with the concrete rather than the abstract. All conceptualising thought about history must encompass people’s lives and their realities (birth, death, love, etc.). Many of those realities are themselves philosophically or epistemologically intractable, resisting any effort to “solve” them. To that extent, it can only be evaluated. As I discussed in one of my previous blogposts for Historica, that evaluation relies on asking certain questions of sources. But those sources necessarily flow from the concrete stuff of historical research.

Rediscovering the Past: Archives, Fragments, and the Limits of Machine Learning

Symptomatic of this bind is a text that approaches the issue from a very different angle. In Jacob’s Room, her 1922 study of a young man’s life before the First World War, Virginia Woolf satirises the type of essay a university student might be set in the early twentieth century: “Does History consist of the Biographies of Great Men?”. To be sure, the invitation is an intellectual exercise, but the title is no accident; it epitomises a stereotypical, albeit at the time largely true, perception of academic historical studies as being keen to pitch male rulers against everything else (or against each other). But for certain periods it also underlines how what survives are the records (diaries, minutes, charters) of those who, at one point or another, were considered “great men”. Unlike the kind of exercise envisaged by the team at DeepMind for mathematical discoveries, however, machine learning in historical research can only create one kind of historical knowledge – to connect the existent, but hitherto unconnected, forgotten or neglected – rather than “discover” something that previously did not exist.

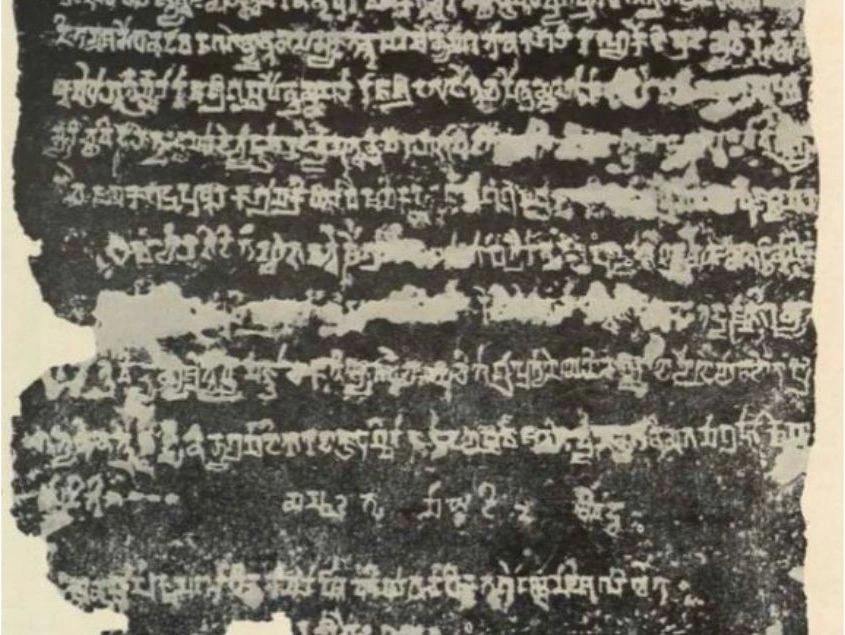

A historian working in an archive, for example, may uncover a document that has previously never seen the light of day. The Genizah documents, for example, include myriad fragments surviving from medieval Cairo that give invaluable insights into daily life stretching back to the eleventh century; they were only ‘discovered’ in the late nineteenth century. A similar cache of material was found in the early 1970s in a cupboard at Ardabil, in northwestern Iran. Recent initiatives have also drawn attention to how complex the idea of the “archive” itself is: historical knowledge does not only reside in texts, but also in less formal contexts (oral histories, collective memories). This notion of recovery, of course, is even more intrinsic to archaeology, which peels back layers to find objects and remains quite literally hidden underground.

Whether textual or material, however, what these examples share is their physicality: they do not exist in the virtual sphere, but only as tangible things that are remarkably fragile. If they are burnt or destroyed without copies being made of them, they cannot be “remade”. The reverse can also be true of virtual sources – for instance those held only on specific devices – despite being “online”. The recent scandal in the UK over ministers’ missing WhatsApp messages is a case in point, and underlines what stands to be lost even in a world where the Internet is ever present in our lives. If such evidence is lost, it must be absent from historical knowledge: unlike in mathematics, intellect alone (human or artificial) cannot make up for it.

Curiosity in Mathematical Inquiry and AI's Response

But to return to the orbit of where I started: in a 2000 lecture, the Fields Medal winner Timothy Gowers posed a cardinal question of different branches of mathematics: “what makes one piece of mathematics more interesting than another?”. The question stems in part from his own interest in combinatorics – namely that it aims to solve specific problems, rather than creating generalising theorising. What I want to focus on, however, is Gowers’ use of the word interesting. Crucially, it is not a word that predetermines a particular use, of mathematics as a tool; instead, it sees these problems as something that appeals to a different sphere of activity – one that appeals to a notably human affective response, interest.

As a (rudimentary and possibly foolish) exercise, I asked ChatGPT 3.5 what it was interested in. Its response was both predictable and revealing: “as an AI, I don’t have personal interests or emotions like humans do”, prompting me if there was a specific topic I’d like to learn about. On one level, this shift back to the user responds to the demands of “intelligence” – to draw limits around its own abilities, rather than over-claiming. The grey area lies between the claims ChatGPT makes about its lack of “personal” interests, and the interests it must deploy in selecting certain facts, for example if it is asked to provide a one-hundred-word summary of a historical event. If the event is well known, it can accomplish that easily. Yet the further it moves away from “facts” – often those connected with the “great men” of Woolf’s irony – the more general it must become to accommodate the request without hallucinating.

The Challenge of Integrating Human Interest with Machine Learning in Historical Understanding

Tying these strands together, the challenge facing all those seeking to employ machine learning and artificial intelligence to understand the past better – including Historica – is how to align human interest with technology that does not seek to solve history, but evaluate it effectively. After all, “discovery” means different things to different people: something that may be a discovery to a particular person may not be a discovery to history. It is that idea of discovery that often sparks interest in a particular period or place, and it remains highly personal: it is why people spend time and money researching their family trees, or browsing photos on Facebook sites devoted to London throughout the twentieth century.

In my next post for this blog, I aim to follow this line of thought further—to ask how increasing awareness of the intersections between the human and the non-human, and between the organic and the non-organic might change this calculation. What happens when machine learning engages with the idea of a posthuman world? If interest in history is as personal as I have just described, does it rely on humans as a discipline? The question is hence perhaps who for? For a system, for an organisation, or for individuals? Answering that question necessarily overlaps with issues of identity and selfhood, but cannot negate the need for anyone (or any programme) concerned with the past to evaluate, rather than solve – and to do so critically, effectively and openly.

.jpg)