Generative AI and the (Tame) Digital History Revolution

Unlocking the Potential of Generative AI in Digital History Revolution

It’s probably hard to know what to do with ChatGPT. Since OpenAI released its groundbreaking chatbot last November, the media’s either heralded it as a revolutionary technology akin to the invention of fire or more often portrayed it as a dangerous plagiarism machine, just the latest technological snake-oil. Yet most people seem to know little about it other than that it allows students to plagiarize essays, that it can spit out good recipes, and write passable Shakespearian sonnets. You’ve also probably heard that it gets things wrong (so-called hallucinations). So aside from frustrating educators during marking season, what could ChatGPT possibly offer those interested in history?

Using Chat GPT in Historical Research

The short answer is that in the very near future, generative AI — of which ChatGPT is just one iteration — will transform how we research historical problems and analyze documents, less so how we write up the results. I like to say that I am an unlikely and inherently skeptical convert as I am a tenured history professor and I love writing — I’ve published many books and articles. But for the past eight months I’ve been working intently with generative AI and writing about my experiences. And the more I play around with it, the more curious and excited I get about its potential. And the things that fascinate me most about the technology have nothing to do with its famous writing abilities. To understand why I am fascinated by AI at the moment, we have to understand how generative AI works.

How Generative AI Works

ChatGPT is a web-based program — a chatbot—that lives on top of a Large Language Model (LLM) that was trained on a neural-network mimicking the structures of the human brain to predict the next word in a sequence of text. This is why some people have called LLMs stochastic parrots and accused them of being plagiarism machines that just reorganize and regurgitate information. But this is not entirely accurate. LLMs are revolutionary because when they were trained on trillions of words of text, they began to do something very unexpected: they started to exhibit capabilities that they had not been trained for like writing, translation, problem-solving, and coding.

Chat GPT's Impact

But it is also why they hallucinate and sometimes get things wrong: they are not recalling information verbatim from a database like a search engine might do and when they don’t know something they tend to provide a convincing but fictional answer. Yet this is getting to be less and less of a problem: as they models get larger and more powerful, they also start to hallucinate less frequently. There is a world of difference in both accuracy and capabilities between GPT-3.5 (the free version of ChatGPT) and GPT-4 (the paid version). If you’ve dismissed generative AI after trying the old ChatGPT last winter, try GPT4 before you give up on the technology.

Few people realize how strange and disruptive this all is: for all intents and purposes, LLMs actually appear to reason. While many in the academic community have dismissed this idea as a mirage, they’ve been equally unable to explain GPT4’s behaviour. While “reasoning” may not be the right word, what fascinates me is that when I ask GPT-4 to do something complex like parsing a series of difficult-to-follow instructions, it usually does just what I asked it to do. While it may be true that the “reasoning” it exhibits is illusory, if it produces an accurate translation of a document I am not sure it matters to most people whether the machine was actually thinking or just doing some really neat stuff that looks like thinking.

Beyond Writing Abilities

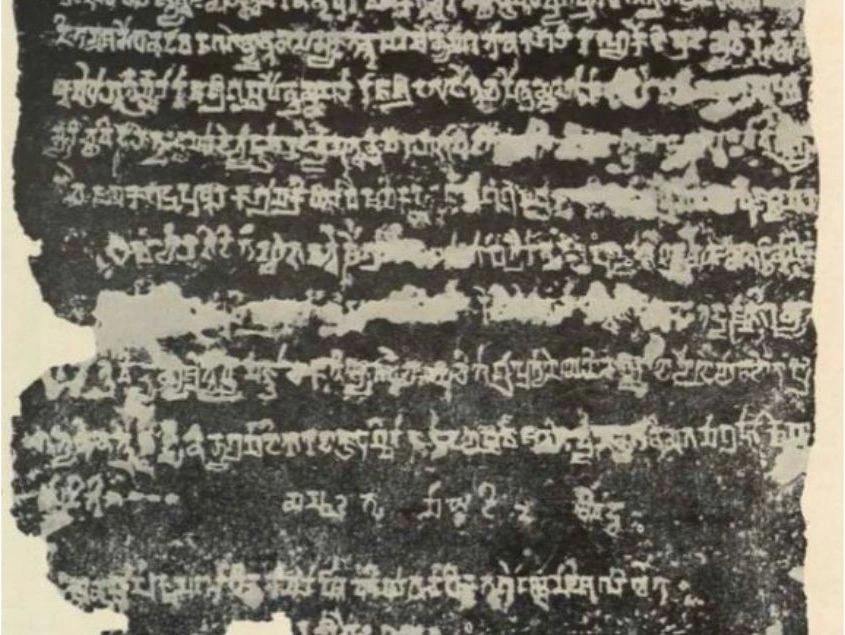

It is this ability to do complex things quickly that makes LLMs so revolutionary. For starters, LLMs are very accurate translators. They can also accurately summarize text, create graphs and charts from data, and even perform their own analysis of things like census records. The predictive capacity of LLMs is also powering new Optical Character Recognition technologies, like the one offered by Transkribus, which can accurately transcribe handwritten documents in a matter of minutes. As an historian, I am most interested in what happens when we bring all of these capabilities together. Very soon we will be able to deploy specially trained LLMs to process large amounts of data quickly, finding references to people and underlying patterns we would never be able to see. This will, in turn, open up new questions that would have been impossible to tackle in the past as well as new ways of doing history.

A Practical Example

Let me provide a concrete example. I am working on a biography of Alexander Henry the Elder, the fur trader. So much of that work involves going through countless ledgers looking not only for Henry’s name but also the names of his business partners in order to understand how his social and economic connections overlapped. Its tedious work to say the least. Now imagine that those records were all digitised. You could certainly perform a series of manual searches — or with a bit of python coding you could ask GPT-4 to map out Henry’s networks automatically.

That would certainly save time! But the amazing thing is that you could then ask GPT-4 to map out all of the business networks for all of the merchants in Montreal between 1760 and 1820, which it could do in a matter of a few minutes. To be clear: it would not write up an analysis of those networks, but you could get it to generate tables, charts, and graphs that you could then work from. Amazing, but let’s take that one step further: using the digitized records of the Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH), it would be possible to map those economic networks onto social networks, looking at kinship networks and social mobility in detail. And if you wanted to visualize the results, you could even ask GPT4 to create a map to show how capital and human-relations evolved in tandem. Apply this to any subfield where we have a wealth of digitized data and let your imagination run wild.

AI's Role in Writing History

If you are worried that AI is going to start writing our history books for us, you can breathe a sigh of relief. It’s a struggle at the moment to get GPT4 to write even 750 words. That’s why the focus on AI’s writing abilities, rather than its analytical and pattern finding capabilities, is so misleading. What excites me about generative AI is that it makes a whole lot of things feasible that would have been impossible or too time-consuming to contemplate a few months ago. With AI, I think we are truly on the cusp of a new digital era in history. But it will be a much tamer revolution than most are predicting, akin to the way digital archival photography altered the research collection process over the past two decades. It will simplify things and speed them up.

.PNG)