Identity and AI: large language models, group dynamics and community building

Exploring the Role of Identity in AI

In my last article, I played a game with ChatGPT 3.5: I asked it what it was interested in. This sort of pointed questioning, I suspect, is familiar to many people as one of the first things they did when the model was first released to the public. The practical tasks that can be accomplished by AI give way to the fun of poking holes in its reality - or at least, in our engagement with its reality – with questions as intuitively simple as “are you real?”. In response, all the model can offer are circumlocutions that betray an inability to “solve” a task that remains fundamentally irresolvable.

To ask questions like this is to raise thorny philosophical conundrums of the kind I don’t want to delve into here, and which boil down to problems of definition: the “real” causes trouble for AI precisely because it cannot be solved beyond the scope of human perception. Where I do want to take this line of thought, however, is towards the question of identity, and whether AI serves to disrupt or reinforce identity as a uniquely human phenomenon.

Identities, philosophical and social

In its origins, of course, “identity” derives from sameness: the Latin identitas that names A as B, and establishes the conditions for doing so. Much Western thought has privileged the capacity to discern sameness – and its converse, difference – as the basis of reason and “intelligence”: only by accurately distinguishing between two or more things can their respective possibilities, applications and uses be identified. Experimental sciences are a case in point. Medicines must target certain cells in the body, otherwise they will not work; to identify the differences between them is a necessary precondition of their effectiveness. This may sound obvious, but is also baked into more problematic ideas of “common sense” when applied broadly: difference becomes the determinant of all relations.

The corollary of this epistemological legacy is identity as understood sociologically. In this sense, identity formation is not immediately about sameness, but about individuality, about tracing the evolution of the self, and comprehending it in relation to others. At heart, sameness underpins this identity too, as a sameness through time (the attributes that make the self the same yesterday, today and tomorrow), and as a sameness in social space (the attributes that make the self the same as other selves). In its expression, it necessarily encompasses the other people that make up our daily lives, as projections of our self: who do we want to be like, and how might that question allow us to become who we want to be?

Group identity, communities and politics

These overlapping strands of entity emerge throughout history as a core function of power: to identify sameness and difference, and to create groups that map on to those distinctions. Some of those identities are claimed and manifested by a ruling class, above all the nation as it emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – to rally around a particular flag, to conceive of the self as part of a community of “citizens”. Other identities are attributed by the ruling class to those it subordinates, either outside its formal borders (above all through colonialism) or within them (in the creation and perpetuation of marginalised groups).

Questions of identity become most potent when they interact with the right to speak, above all to speak for a particular community. Recent attention has focused on a professor at UC Berkeley who claimed indigenous American ancestry despite lacking any evidence for it. Communities historically excluded from the body politic can find common cause to reclaim their shared identity, as a site of resistance to a majoritarian identity that refuses to accommodate it. Those communities are not exclusive: as Kimberlé Crenshaw has shown, identity is intrinsically intersectional, however much individuals may adhere to certain identities over others. The point – even from this brief summary – is that identity cannot be boiled down to a single sameness of its own. It is that complexity that AI risks stumbling into, without being cognisant of the possible consequences.

Historical identities: generating something from nothing?

A good example of this risk – not least in relation to the past – was recently revealed by Google DeepMind’s Gemini model, which was asked to create images of, among other people, a “Founding Father of America”; in response, it generated several images of people of colour, including an image of an indigenous American. The original prompt had come from an account on X (Twitter) called “End Wokeness”, which sought to promote the idea that Google had introduced some form of bias against white people into its image generation software. The irony was clearly lost on those manufacturing disbelief around these images: that the pictures instead offered a much deeper truth about the racial injustice that accompanied the foundation of the United States, of the kind traced by the New York Times’s 1619 Project.

To a certain brand of X user, of course, this kind of conversation is merely an excuse to bring their own deep-seated prejudices to the fore, to add ever more fuel to the “culture war”. To me, however, the most striking question raised by Gemini’s images is not cultural at all, but historical: what were the conditions that made it impossible for any of the “Founding Fathers” to be people of colour? History is concerned with articulating those conditions, rather than determining an absolute version of the past.

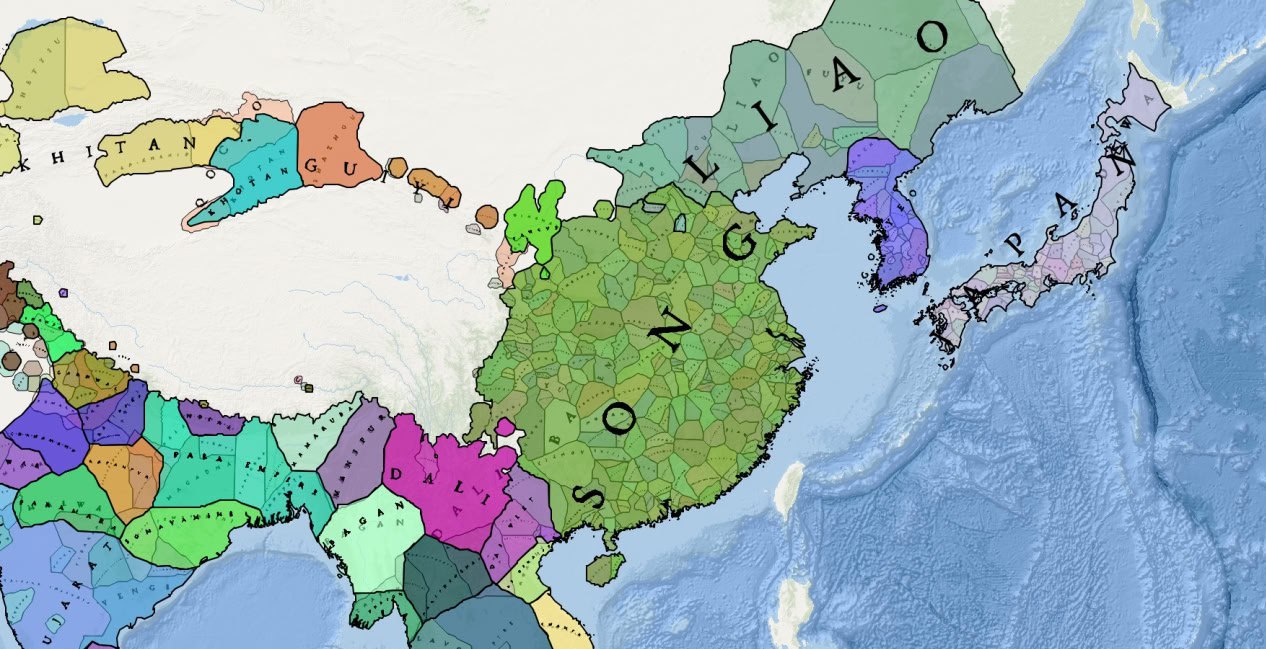

At the same time, the perspective espoused by “End Wokeness” also fails an explicitly fact-centric view of history. The account also asked Gemini to generate images of Vikings, who are also shown as people of colour; yet only if the Vikings are assumed to be homogenised replicas of ABBA, “archetypal” Scandinavians with blonde hair and blue eyes, is the generated image somehow “inaccurate”. It is, above all, to associate the Vikings with a particularly ethnocentric idea of Europe, negating their position, for instance, as arbiters of long-distance trade between Central Asia, the Middle East and northern Europe. In different ways, these two examples of Gemini’s output illustrate a core test for AI models: they are themselves subject to human biases of what is “right” and “wrong”, biases that quickly take on a life of their own in a time of social media. In other words, the sections of X that sought to discredit Gemini – partially successfully, given Google’s later decision to alter the programme – were attributing an identity to it. But that identity, far from being generated by the software itself, was still all too human.

In search of nuance: paths and connections

In and of themselves, then, large language models cannot possess a single “identity”, precisely because they are imbued with the variety of human experience and opinion. In a world still rife with prejudice, this is hardly unsurprising: software is trained on raw material will tend to perpetuate what it is fed. What is striking about the Gemini maelstrom is that the images generated seem to be trying to guard against replicating biases of the kind that can have real-world impacts – as seen elsewhere with facial recognition tools.

In this context, and despite the scenarios advanced about AI’s capacity for sentience, it is difficult to see how a discrete sense of identity might emerge. In his 1984 book Reasons and Persons, the philosopher Derek Parfit distinguished between a widely drawn “personal identity” – as sameness over time – and what he calls “psychological connectedness”, for him the thing that “matters” in what we label identity. It is important to distinguish Parfit’s conception of identity from its use as a sociological marker, but I would suggest that his invocation of “connectedness” may offer a glimmer of hope to both kinds of “identity”. The challenge is what to do when humans seek to disrupt all sense of connectedness, in favour of a worldview that emphasises difference and disconnection. What I have sought to show here, however, is that meeting that challenge remains an essentially human task to strive towards that goal: AI cannot simply do it for us.

.jpg)