Machines talking about art: language versus communication models

The Timeless Language of Visual Art: Communicating Through Centuries

Works of visual art are among the first attempts of human beings to express themselves and probably to leave a long-lasting message, so that artistic expression has been considered as an inherent need. In its long history, human kind as always used art as a communication medium with its peculiar aspects: on one hand easy to understand because it is visual, on the other hand not based on a unique code of interpretation. Moreover, art requires a skillful use of techniques (it’s probably useful to remind that the Latin word ars means, above all, technique), a talent but also knowledge and experience to express a message, to stimulate emotions and feelings. Works of art are therefore fascinating human beings since ever, so that we are continuously looking for a deeper understanding, a better knowledge of their principles.

Even this short introduction leads us to imagine the richness of possible interpretations of a single work, what then when we face many of them in the same place and we understand they they can talk to each other so creating a net of relationships that seems to widen and multiply the message?

Museums as Complex Communication Systems: Enhancing Visitor Engagement

That’s what usually happens in historical buildings or in museums, where visual stimuli become protagonists of a complex communication. The definition provided by the International Council of Museums states that “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity, sustainability and citizen curation. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.”.

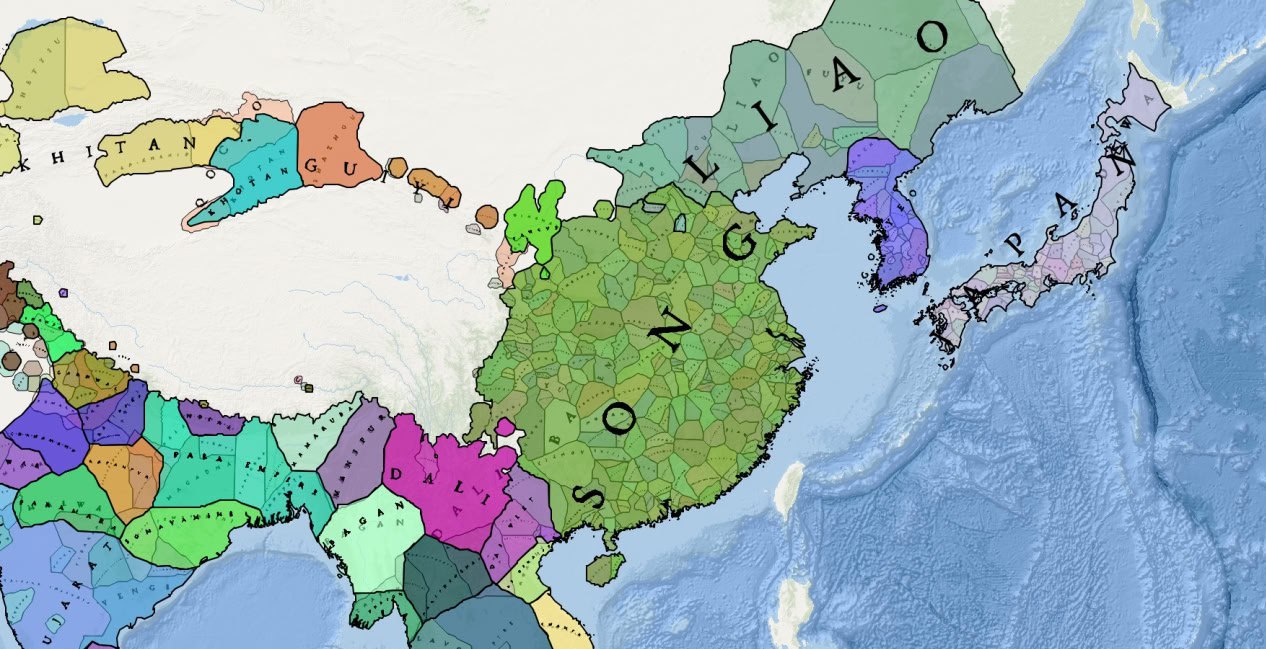

Furthermore, if we refer to the wider idea of heritage, the concept of “education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing” remains fundamental. Ideally, technology should be employed to support cultural environments in achieving the mission stated before. According to the museum studies literature, the definition of museum as a Communications System refers to every kind of museum and includes every aspect: exhibits, their selection, the set-up, the lighting, labels, educational programs, videos, and whatever contributes to communicate a message related to the museum itself. Even considering such an articulate system, some museums show peculiar aspects that make them complex, i.e. when beyond the museum function of form and content, they are monuments in themselves. The nature of monument implies, on one side, historical aspects, a notable architecture, with decoration and often even remarkable works of art stratified over times. Usually, all these aspects are kept together by centuries of history that contributed to merge all of them by multiplying and enhancing the sense. In other words, the whole environment, in its complexity, plays a role in the process of creation of sense.

The Intersection of AI and Cultural Heritage: Redefining Virtual Experiences

Modern technology can intervene on these aspects like never before, as the modern era has seen dramatic improvements in the field of Natural Language Processing and Conversational Artificial Intelligence, with Large Language Models (LLMs) attracting a great deal of interest. As powerful as this new technology is, however, it is necessary to correctly frame it in the context of Artificial Intelligence and understand its capabilities and limitations to be able to correctly deploy them. Humanities studies play a significant role both in understanding what conversational architectures based solely on generative approaches can do and what is simply beyond their reach. From a linguistic point of view, for example, it can be argued that LLMs model surface aspects of communication but fail to capture the deeper motivations and intentions for communicative acts. In other words, a Language Model, capturing complex regularities in words use, is not a Communication model, capturing the reasons why words have been produced. These aspects find correspondence in the AI field, particularly when considering the Ladder of Causation from Judea Pearl, where the difference between observation and prediction capabilities are considered inferior with respect to intervention capabilities. For a full discussion about this topic, we refer to the Conversational AI series found on the URBAN/ECO Research Center (University of Naples Federico II) blog.

Advancing AI in Cultural Heritage

Museum studies have extensively investigated the strategies for exhibit design and museum space usage, also considering the difficulties coming from some museums also being historical buildings. Moreover, visitor studies have investigated multiple aspects of people’s behaviour when they are found in cultural environments. While these models have been used, in the past, to motivate technological interventions in museum environments, they have rarely been used to drive the design of the communicative intent of exhibits. This is, of course, understandable on multiple aspects: first, a public institution cannot delegate its communication design to technological artifacts of the current generation. Also, the same artifact may serve different roles in the design of different exhibits depending on characteristics that may very well be mostly visual rather than textual or catalographic. Moreover, balancing communication needs with budget, space and lighting constraints further complicates the task, leading to a situation where specific competence coming from domain experts is needed to understand how to deploy currently available AI tools.

A particularly interesting case is represented by virtual spaces, where Conversational AI technology paired with the use of Virtual Humans can surpass the limitations of physical spaces and real-world constraints, providing an insight into the world of history and art that may fuel user motivation into visiting cultural sites. When photography became widely adopted, the availability of the images of cultural artifact was first seen as a threat for museums, as people may have chosen not to visit them because they could see the reproduction more easily. This turned out to be the opposite: people were motivated to go see the original because they appreciated the reproduction. Current technology may serve a similar purpose, today, as multiple objects may be presented as part of a coherent communicative intent that can only be described in a computational model by collaborating with cultural heritage experts. At the same time, the use of cultural artifacts reproductions and natural language aimed at producing positive changes in the society calls for new AI paradigms.

The Limitations of LLMs: Understanding Intent Beyond Language Generation

While LLMs, in fact, have shown exceptional capabilities to produce fluent language, they fail in understanding both goals and consequences of what they are doing. Being very powerful Natural Language Generators, in this sense, they need other AI modules, deciding why to say something, to instruct them in what to say. These aspects can only be modelled based on a deep understanding of cultural communication models, which is a topic humanities researchers have studied for decades. These communication models, then, must be interpreted in a technological framework general enough to avoid being tailored for a specific task, since the goal is to build machines that communicate, in general, rather than industrial tools. Embodied communication, in this sense, is particularly important as both speech and body language are relevant for the case of cultural heritage presentation in virtual tours. For the specific case of Virtual Humans, for example, deciding what to say, how to say it and how to complement the provided information with relevant movements, like pointing movements, is critical for a successful presentation. Previous work has shown that Virtual Humans used to provide introductory presentations to visually rich cultural sites help people identify important details autonomously. Moreover, a linguistically motivated use of different kinds of pauses in synthetic speech is important to help people memorise information.

This research is currently being conducted at the URBAN/ECO Research Center, at the University of Naples Federico II, and builds upon the experience of the Cultural Heritage Resources Orienting Multimodal Experiences (CHROME) research project, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research. The technological framework used for this research is the Framework for Advanced Natural Tools and Applications with Social Interactive Agents (FANTASIA), which architecture is shown in the following Figure. FANTASIA allows to inspect deep aspects of decision making using multiple AI tools. This allows to keep the AI models explainable, so that every decision they take can be inspected by the developers. It also allows to develop and test communication theories using humanities studies, which hold great significance in the development of human-like intelligence going much beyond statistical learning. Our experience with communication tasks based on the use of Natural Language tells us that, in an era where human-like intelligence is more sought than ever in machines, humanities research has great value in defining the guiding principles to help machines better understand what it really means to speak, going beyond merely generating words.