The Impact of AI on Historiographical Storytelling and the Risk of a Selective, Eurocentric Narrative

Ever since Artificial Intelligence entered our lives, we have begun using it as if it were a trustworthy oracle, capable of providing us with real-time information about everything.However, the idea that AI represents a profound and comprehensive understanding of the complexity of our world is one of the greatest illusions we have ever been told.

The fault for this bitter truth does not lie with technological advancements or progress in machine learning—far from it. In an increasingly globalized world, technology allows us toobserve both what moves forward and what is left behind. And yet, despite the progress of the last twenty years, geopolitical relations have remained largely unchanged. The deep-rooted connection between colonizing and colonized countries continues to influence the societies of the latter in ways that are still tangible today.

This flawed, incomplete, and biased narrative of the world is not only accepted as legitimate but continues to dictate the standards by which global history is written and understood.

We must therefore ask ourselves: where did we abandon ethics in the writing of history? More importantly, what can we change today to ensure that artificialintelligence plays a responsible role in this process?

The Importance of Postcolonial Studies: A Crucial EthicalFramework for AI in Historical Research

Postcolonial studies maintain a complex and often paradoxical relationship with Western political and social philosophy. On the one hand, they acknowledge its influence—deeplyingrained in customs, habits, and society—while on the other, they critique its intrusiveness, inauthenticity, and inequality. These studies attempt to restore the originalpolitical and cultural identity of nations that have experienced colonization, offering a more complete and less assimilationist version of history.

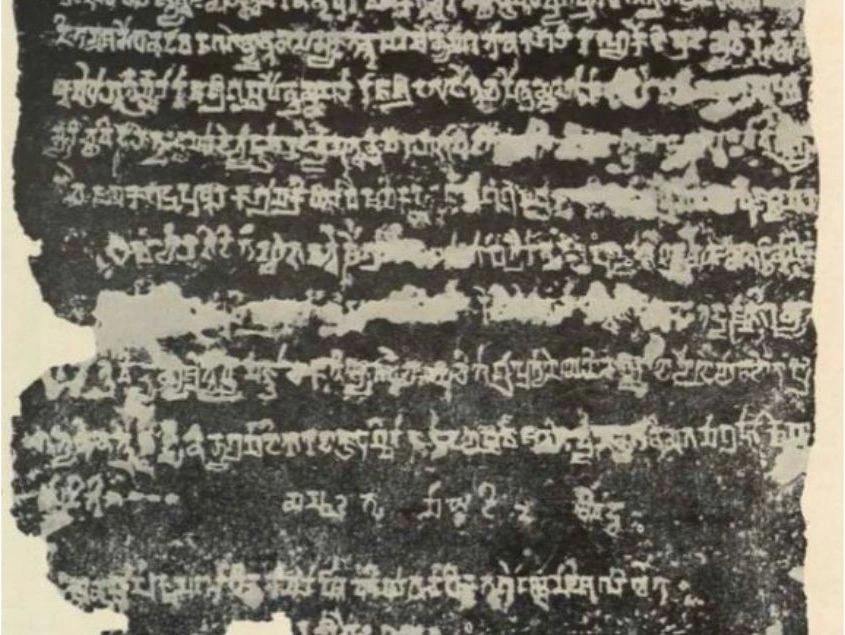

By doing so, we can give these countries an identity beyond the one imposed by the dogmatic Western narrative, highlighting what stems from their internal evolution and what is a consequence of colonial oppression. Prominent figures in postcolonial studies, such as Aijaz Ahmad, Edward Said, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, have long emphasized how history has been written from a limited perspective—using texts primarily in the hegemonic languages of the colonizing nations.

This selective approach is mirrored in the machine learning models we interact with daily, often believing we are accessing a truly democratic and unbiased source of knowledge. Inreality, AI models inherit and reinforce the biases embedded in our Eurocentric cultures—making them, by extension, racist, imperialist, and sexist.

How Can We Ethically Reshape AI in Historical Research?

If AI is to play a meaningful role in rewriting history—both present and future—we must critically examine the data we provide to train it. Blindly accepting a Eurocentric worldview as the only valid perspective is not just unethical; it is also a convenient way of maintaining these power structures. Mathematician Cathy O’Neil has extensively discussed how AI bias is not just a technological issue but a deeply political one.

There are tangible solutions to this problem. We could clean up and diversify the datasets used to train AI. We could integrate texts from countries that have historically been excluded from mainstream historiography. We could redefine the frameworks used to assess merit and representation. Most importantly, we could finally amplify the voices of societies that have long been sidelined in global discourse.

My concept of "fair" aligns closely with "equal"—and in the field of historiography, I would even equate it with "representative" and "truthful." Unfortunately, much of the history we have recorded so far cannot claim to meet these criteria.

To move forward, we must create new AI models that learn from a broader spectrum of realities—models that do not merely tolerate diversity but recognize and embrace it as a strength.

Conclusions

As long as AI models remain unaltered, they cannot be ethically used for the rewriting of history. Any attempt to do so under current conditions would only reinforce an already skewed narrative—one that prioritizes certain texts, written in the languages deemedworthy" of recognition, while silencing others. The result would not be an inclusive and representative history but yet another iteration of a world that amplifies dominant voices while suppressing those that mainstream discourse prefers to keep unheard.